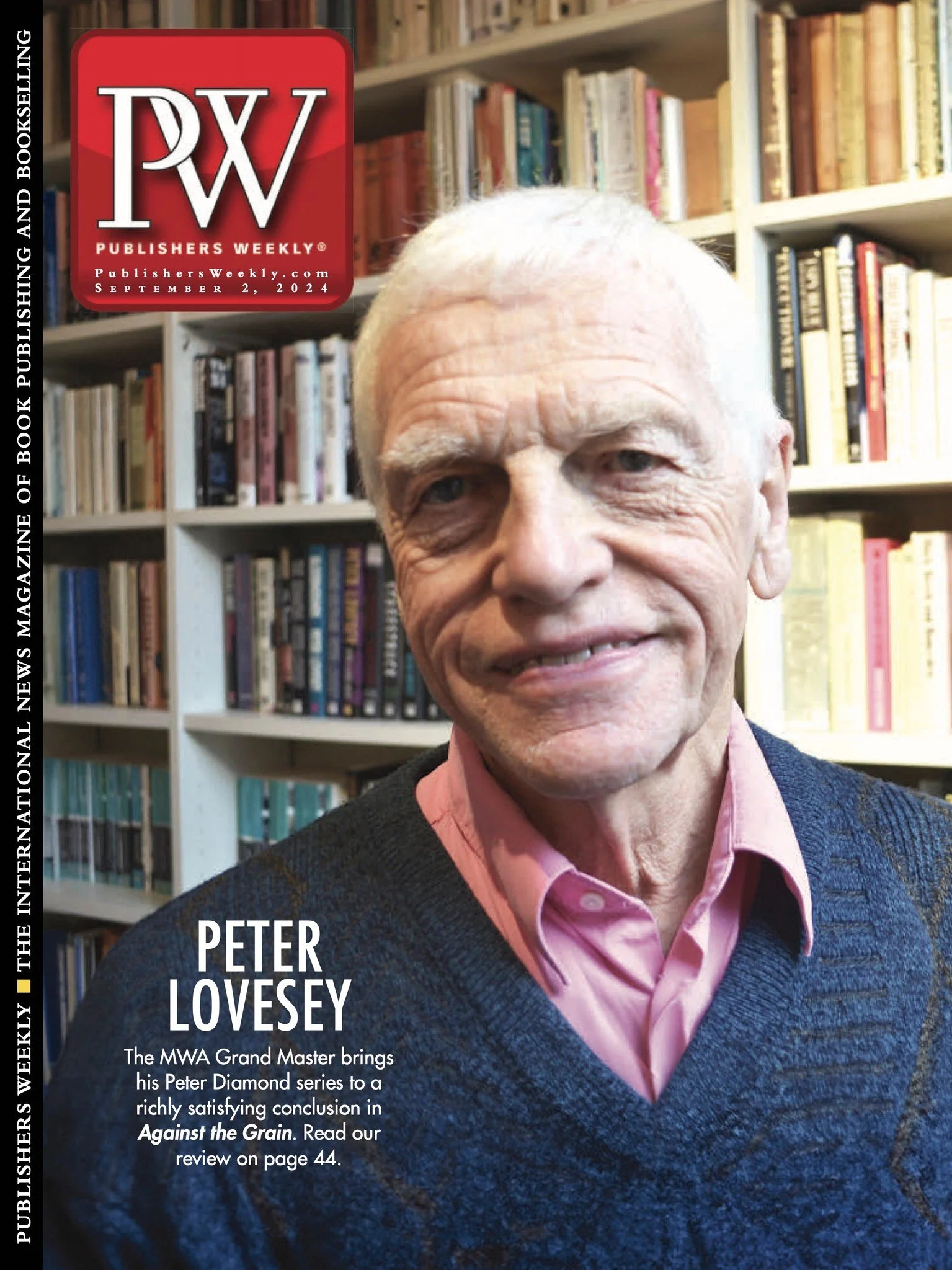

The legendary Master of Mystery, Peter Lovesey, weighs in on the novels that began his career in mystery and the novel that ends his long-running series with Peter Diamond.

Interview with Peter Lovesey

The last in the Peter Diamond Mystery Series

set in Bath, England

“Never to fall into the trap of repeating a plot. You need to plunge your main character each time into wholly new circumstances.”

"I get the ideas wherever I can and spend time mulling them over until I have the makings of a plot."

Why did you decide to switch to the present day with the Peter Diamond series, set in modern-day Bath?

It took me over twenty years. I needed the confidence of knowing my topic well and I was more in touch with police procedure in the 1880s than the 1970s. The Sergeant Cribb books became a series of eight covering various Victorian enthusiasms such as boating, holidays by the sea, bareknuckle boxing, spiritualism and the music hall (vaudeville). I bought old books and kept a card index of such things as costume, transport and slang. I did more books that were set in the past. And then I returned to running as a theme and broke out with a bestselling book that was more suspense than mystery called Goldengirl, about a Californian superstar hoping to win three gold medals at the 1980 Moscow Olympics, and how she had to suffer the commercialism, exploitation and the temptations of hormone treatment. Hollywood made it into a not very good movie, and I was paid enough money to convince me that I ought to do more writing set in present times.

You’ve written several series, but your longest one is the Peter Diamond series. What are some of the challenges you face in maintaining a lengthy series?

Never to fall into the trap of repeating a plot. You need to plunge your main character each time into wholly new circumstances. In the second book, Diamond Solitaire, he has left the police and is travelling, trying to solve the mystery of an abandoned autistic child. By book six, I realized the series was getting too cozy, so the next one, Diamond Dust, starts with the murder of his beloved wife, Steph. Even in book twenty-two, the latest, he is ripped out of his familiar police office and goes undercover in a village murder case.

Your Bertie, Prince of Wales Mysteries feature a royal as a detective. Were you or your publishers worried about any backlash from the royal family or devoted Royalists?

At the time I wrote about Bertie it was a bit of a risk. We Brits were still too reverential about the royals. However, Bertie had always had a saucy reputation that biographers had already put on record. I decided to go the whole hog and write the books in the first person, from his point of view. But comeuppance threatened when I was vice-chairman of the Crime Writers’ Association and Princess Margaret was Guest of Honour at the awards dinner. She seemed to know about the books and thought them “rather amusing” so I wasn’t arrested for treason.

You’ve written three novels under another name, Peter Lear. Why did you make this choice?

The book I mentioned above, Goldengirl, set in the near future, was such a different story from my Victorian series that I felt my regular readers would feel conned if they bought it expecting to read about Sergeant Cribb. Similarly for Spider Girl and The Secret of Spandau.

What’s on your To Be Read pile ? What types of books do you like to read? Favorite authors?

I find as I get older that friends send me their books and I don’t have time for much else. My all-time favourite author was another friend, the late Donald E Westlake. His Dortmunder series about a small-time crook with big ideas that almost work out is the funniest I know. And he also wrote a superb hard-boiled series under the pen-name Richard Stark. The best-known, called The Hunter, was filmed as Point Blank.

What was your road to publication? What was your first novel?

It was more of a backstreet than a road. From my early teens I took a strong interest in the history of track and field athletics and wrote magazine articles I researched at the British Museum newspaper library. Eventually in 1968 I wrote a non-fiction book called The Kings of Distance that was accepted for publication. It was picked by World Sports magazine as the sports book of the year, I think because it was new material and totally different from other sports books. I was thrilled, but couldn’t see myself ever writing another until we saw a small-ad in The Times offering £1000 as the prize in a first crime novel contest - more than I earned in a full year as a teacher. I knew little about mystery writing apart from the Sherlock Holmes stories, but my wife Jax suggested I used my nerdish interest in nineteenth century running to devise a plot that would be original, if nothing else. I wrote Wobble to Death in three months and - drumroll, please - I won the prize.

"Wobble to Death" and your subsequent Sergeant Cribb novels were historical mysteries set in Victorian England. What interested you about the Victorian era, and why was it a good setting for crime?

Those mustachioed athletes in long shorts going round a small track for six days had to be prime suspects in a murder case, along with their trainers, managers and lady friends. I went back to the newspaper library and really got to know the subject in detail. Victorian reporters were paid a penny a line for their reports, so they stuffed in as much detail as possible to earn their crust. They also wrote vividly on crime - and there was plenty of that, at a low level that I could exaggerate. Some trainers would sabotage the rival runners by putting walnut shells in their boots or adding strong laxatives to the soup they drank. For laxative read ”poison” and you have a murder.

How do you keep the stories fresh while staying true to the character?

If the character lives in your imagination, you get to know how he or she will cope with anything, be it dismissal from the job, the loss of a spouse or helping a cow to give birth, as he does in Against the Grain.

Which authors influenced your work?

Arthur Conan Doyle for introducing me to the Victorian period; E L Doctorow for his sense of period and narrative drive; and Patricia Highsmith for her innovative plotting.

Some questions specifically about one of your books:

Your novel "Diamond and the Eye" was about the discovery of a valuable piece of art. Why do you think art makes a good plot line in a mystery or crime novel?

I have always been excited by art. It got me into university for a degree in fine art. My best work there was a lifesize caricature on rag day of the professor of English, who persuaded me after a year to change my course to Eng Lit. I have used art in different ways as a background in several of the books. If you know something well, you will find a way of writing about it.

"Rough Cider", told through the eyes of a child in WW2, has been called by many your finest work. Did you draw upon your own personal memories in writing it?

Yes, it was closest of them all to my real life. In World War 2, we were bombed out and my mother and we three boys were billeted to a farmhouse in Cornwall where the farmer and his wife were forced to put up with these cheeky London kids. When we returned to London, I was treated generously by some GIs who were stationed there. The memories were blended in the book, but I didn’t really witness a murder.

Do you have a favorite book or series you’ve written?

I’ve discussed the series in my responses,, but I am proudest of some of the stand-alones, notably The False Inspector Dew and The Reaper.

And finally…

Since you’ve been around the publishing industry for many years, what are the biggest changes you’ve seen (good or bad)?

Bad: I miss the long, expensive lunches and tea at the Ritz fifty years ago, but I expect other better-known authors still get treated. Good: when I started, almost all the mystery books in the UK were published by three or four major houses, but now new authors have the chance of showing their scripts to numerous independent publishers or even making a success of self-publishing.

Several years ago on a conference panel you recounted a neighbor, who had seen you taking a walk, saying she didn’t want to disturb you “in case you were thinking.” Is that when you plot? What is your writing routine?

I get the ideas wherever I can and spend time mulling them over until I have the makings of a plot. When I started, I needed the prop of a complete chapter–by-chapter synopsis. These days I start with a looser framework, but I still want to be sure I have a plot that will work. I’m a slow writer (200 words a day on average), but I don’t work in drafts. Only rarely do I go back and change anything.